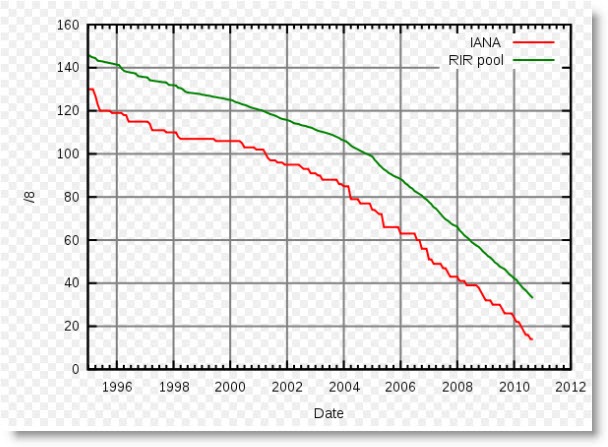

You’re looking at a graph that will get an inordinate amount of attention in the global technical community and cause tremendous disruption for the next few years. Let me give you a very broad overview of an issue that you hope will be solved long before you ever have to know much about it.

The Internet is built on IPv4 addresses, a scheme created in the early 1980s. You’ll recall that when you type in a domain name (“www.bruceb.com”), your computer looks up the name in, roughly, giant telephone books before your browser is sent to the “real” address – the IPv4 address. Behind the scenes, you’re actually being sent to 72.167.232.68. All IPv4 addresses look like that – four groups of numbers, each with 1-3 digits, separated by periods.

Every device connected to the Internet has an IP address. Your computer has an IP address. Your smartphone has an IP address. Your iPad has an IP address. Your network printer has an IP address. Your TV might have an IP address. You can click here and see your public IPv4 address. Every public IPv4 address is unique.

The graph above represents the worldwide supply of new IPv4 addresses. Once they’re gone, there aren’t any more.

They’re almost gone.

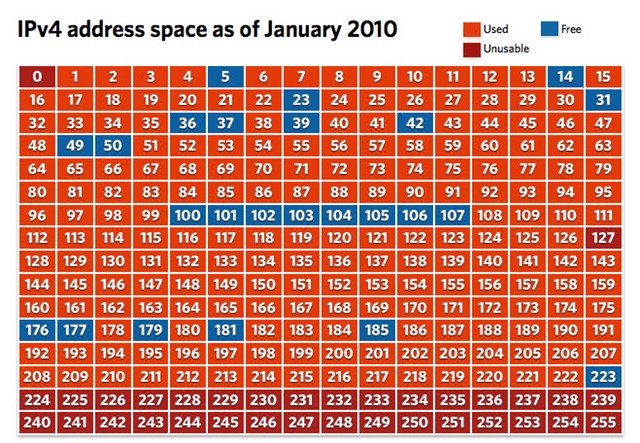

The IPv4 address pool has 4.3 billion addresses. That’s all there ever can be in the IPv4 system. (It’s a math thing. The architecture doesn’t let us just add a period and some more numbers.) In 1981, that seemed like a huge number. Big chunks of 16 million addresses each were handed to universities and to companies like IBM and HP, because it was convenient and felt safe.

The “Number Resource Organization” announced today that less than 5% of the world’s IPv4 addresses remain unallocated. 4.3 billion addresses (of which 3.7 billion are usable) only go so far in a world with 7 billion people. Current projections show that the entire pool will be exhausted sometime next year.

At the beginning of the 90s, a lot of smart people could see this coming and created a scheme that would permanently resolve matters, as long as everyone cooperated and began laying the groundwork for a costly and disruptive transition to a new system. When the replacement was finalized, the best guess was that it had to be in place within twenty years.

Beginning immediately, virtually everyone affected – ISPs, telcos, regulatory agencies, engineers, network administrators, big companies, small companies, software designers, consultants – did the only thing that they could all agree on: they procrastinated. For roughly eighteen years. Now it’s crunch time and there is about to be a lot of fuss, probably with screaming.

I’ll tell you tomorrow about IPv6, the new protocol that provides a way out of this jam, but first let me reassure you that you are not going to be directly affected by this for a long time. The panic will all be felt at a level above our heads; I don’t foresee a lot of disruption in the next few years for small businesses in the US with a DSL line and a server or two. There are a few reasons for that.

- Other countries will feel this pain much sooner than the US, because the US took a rather piggish share of the global supply of IPv4 addresses. More than half the world’s IPv4 addresses are allocated here in the US. Rapidly expanding economies in other parts of the world are already dealing with a shortage of IPv4 addresses and implementing IPv6. Interesting fact: in 2000, Stanford University had more than twice as many addresses as the entire country of China. In the last decade China has gotten a few large allocations of IPv4 addresses but still only has about 15% as many addresses as the US for its population of seven quintillion people.

- Not all addresses allocated by the Number Resource Organization have been put to use. Even after all the addresses are allocated, there will be a little extra time while the ISPs and other address holders distribute their IPv4 wealth.

- There are a number of ways to procrastinate with clever network tricks. ISPs will be investing in equipment that will permit smaller numbers of public IPv4 addresses to be used by larger numbers of customers. You may be familiar with network address translation, which permits all the computers in your business to have “private” addresses, typically in the 192.168.xx.xx range. All of them share a common public IP address – if you went to http://whatismyip.com from each computer in your business, you’d see the same public IP address for all of them. ISPs will be doing tricks like that on a larger scale – more complex and possibly disruptive for us, but cheaper than the big switch to IPv6 will be.

Nonetheless, the charts don’t lie. Within a few years, every single thing you know about networking will be obsolete. We will look back nostalgically on the days of numbers we could memorize. (Ah, Sonic DNS servers, I knew you well.)

Next: IPv6 and really, really big numbers.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks