There is a difference between Russian hacking, on the one hand; and Russian meddling in American society and interfering with our election, on the other hand. The terms are used interchangeably and imprecisely in news coverage. Let’s try for clarity. Knowing the difference will help you sort out the claims flying back and forth in the headlines.

This is a very general, very brief overview of three things.

• What is hacking?

• What is “meddling” and “interfering”?

• How does the United States know about Russian hacking and meddling?

What is hacking?

Hacking is breaking into a database, a computer, or a network that you do not have permission to use.

The term “breaking into” covers a lot of different activity.

One example: A hacker might send a phishing message to obtain a password to an email account. The hacker can then read all the mail and see everything in the mailbox. This is how the Russians hacked the mailbox of John Podesta, the chairman of Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. Similar phishing messages are flooding into your inbox.

Another example: A hacker might use stolen passwords, viruses, or security vulnerabilities to gain access to entire networks.

Hacking can be used destructively. This is the traditional definition of hacking – viruses that break computers, ransomware that destroys data, or hacking that compromises databases, resulting in identity theft and financial loss. It might be done for money, for political purposes, or just to be malicious.

• Russia hacked into the computer systems in the Ukraine and shut down the country – literally turning off the lights and disabling a third of all the computers in the country at the same time.

• North Korea hacked into Sony’s network and disabled all the computers in the company at the same time.

• The United States hacked into Iranian nuclear facilities and damaged equipment.

Hacking can be used to obtain information without causing any direct damage to the computers that are hacked. Nations do this for intelligence; companies do this for economic gain.

• Russia hacked the Democratic National Committee and obtained all the data on email servers, backup servers, VOIP calls, chat logs, and more. Russia also hacked into the DNCC, hacked into John Podesta’s mailbox (among others), and sought to hack into state voter-registration databases.

• Edward Snowden hacked the NSA and obtained gigabytes of high-level overviews of secret NSA intelligence activity.

Hackers may also implant code that is not immediately active but can be activated later. For example, Russians have implanted code in hundreds of US electric utilities.

Russian hacking is only a small part of the investigation into the US 2016 election campaign. Mueller’s investigation covers Russian hacking into Podesta’s email and into the DNC and DCCC networks, but that is only the beginning. The investigation is primarily about how the information obtained from those hacks was used by the Russians, and about other Russian acts intended to disrupt the United States and influence the 2016 election.

What is “meddling” and “interfering”?

Under Putin’s leadership, Russia determined that political divisions in the United States were ripe for exploitation. Posts on social media could incite disagreements, fray social bonds, and drive people apart. Although these techniques were used during the 2016 election campaign, and specifically used to favor Trump over Clinton, the Russians had and have a larger goal: to pull at the threads that bind a society together.

Dividing Americans from each other and increasing the rancor of our partisan battles was and is the goal of Russia’s disinformation campaign. This is what we mean by “meddling” in American affairs. Putin seized new digital tools and set out to use them to “hollow out a state, gradually degrade its institutions, and undermine confidence in everything from election boards to the courts and the embattled local governments,” as Sanger describes it in The Perfect Weapon. The Russians attempted to manipulate election results, created fictional online personas who widen social divisions and stoke ethnic fears, and distributed misleading and false news.

Russia’s propaganda center, the Internet Research Agency, was operating on a multimillion dollar budget by 2013, employing news writers, graphics editors, and SEO experts. It has generated tens of thousands of tweets, Facebook posts, and advertisements in hopes of triggering chaos in the United States by spreading misleading or false information and amplifying specific hashtags and threads. Twitter reported in January that it found 50,000 Russia-connected accounts, which reached nearly 700,000 Americans.

Understand, then, that some of Russia’s efforts had nothing to do with the election. Russia sought to create chaos and to exploit any divisive issue in American society where a wedge could be driven via the Internet, to widen the natural fault lines in American politics and society.

• Sanger tells the story of one successful project involving a phony group created by the Russians, “Heart of Texas”: “They promoted a rally called ‘Stop Islamization of Texas,’ as if there were much Islamization to worry about. Then, in a masterful stroke, the Russians created an opposing group, ‘United Muslims of America,’ which scheduled a counter-rally, under the banner of ‘Save Islamic Knowledge.’ The idea was to motivate actual Americans – who had joined each of the Facebook groups – to face off against each other and prompt a lot of name-calling and, perhaps, some violence.”

• Messages were sent to residents of St Mary Parish, Louisiana, warning of a toxic fume release from a Columbia Chemical plant – a plant that did not exist.

• Rumors were spread that Ebola had been discovered in parts of the US, with fake news and video accounts.

This project was not limited to the United States. Russia used, and continues to use, the same techniques to sow dissension in other countries.

• Putin practiced his techniques in the Ukraine. When we were warned earlier this year about a vulnerability in our routers, it is not a coincidence that the Ukraine was the target of most of the attacks.

• Russia released a YouTube video recording of a hacked phone call by an American assistant secretary of state that appeared out of context to be critical of EU allies, to create distrust and perhaps cause a breach in the relationship between the United States and the EU.

• The New York Times reported today, July 29, 2018, on the findings of a British committee investigating Russia’s role in encouraging Britain’s exit from the EU: “Moscow has long sought to weaken the European Union, and the committee’s report cited research showing that in the six months before the referendum in June 2016, the Kremlin’s English-language outsets, Sputnik and Russia Today, published 261 articles supporting Britain’s withdrawal from the bloc. Those articles then somehow reached more users on Twitter than the content produced by the two main campaigns for Brexit.”

The 2016 election campaign

Russia generally wished to increase polarization in the US. One way it chose to carry that out was to favor the election of Donald Trump and cause dissension among Democrats. At about the time of Trump’s inauguration, U.S. intelligence agencies published a report that concluded that “Vladimir Putin and the Russian Government aspired to help President-elect Trump’s election chances when possible by discrediting Secretary Clinton and publicly contrasting her unfavorably to him.”

The Russians used a fake identity, Guccifer 2.0, to distribute selected portions of the material it had obtained by hacking into mailboxes and mail servers. The US intelligence report highlighted two Russian reports on YouTube that received millions of views, one titled “How 100% of the Clintons’ ‘Charity’ Went to . . . Themselves” and the other, “Trump Will Not Be Permitted To Win.” Russia created and promoted more than 100 different events on Facebook and spread misleading and false information on Twitter, including many items that were retweeted or engaged with by members of Trump’s campaign team.

Russians spread falsehoods about Hillary Clinton’s health. They spread a story that members of Clinton’s campaign were engaged in a child prostitution ring. They attempted to increase tension in the Democratic party by selectively leaking emails to make it appear that the deck was unfairly stacked against Bernie Sanders. Russians hired an actress to attend a Florida Trump rally dressed as Hillary Clinton in a prison uniform.

The Washington Post just reported on one recent discovery: the day before Wikileaks began releasing emails hacked from Hillary’s campaign chairman, Russia operatives fired off more than 18,000 tweets toward American voters. “Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump: Which one is worse: Lucifer, Satan or The Devil?” said one tweet that directed readers to a YouTube video. We don’t know the specific reason that Russia chose that to be its busiest day on Twitter. As it happened, it was also the day that US intelligence officials first made public their growing concerns about Russian interference in the US election – which was overshadowed by the release on the same day of the recording of Trump’s comments about grabbing women.

In its article about the discovery of the tweet storm, the Washington Post reports that 230 Russian Twitter accounts sought to infiltrate left-wing conversation but “did so in a way clearly designed to damage Clinton, who is portrayed as corrupt, in poor health, dishonest and insensitive to the needs of working-class voters and various minority groups. By contrast, the Left Trolls celebrated Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and his insurgent primary campaign against Clinton and, in the general election, Green Party candidate Jill Stein.”

There is no question that Russians attempted to interfere with the 2016 US presidential election. There is detailed evidence about it. That’s why every report about it from US intelligence agencies and from joint Congressional committees has agreed that Russian attempts to interfere were quite real and quite serious.

Of course, the Russians were not the only group with an interest in increasing polarization in US society. Obviously the Russians were not the only ones seeking the election of Donald Trump. Trump’s campaign would have had good reason to highlight the same issues and pursue the same techniques to flood social media to promote Trump’s candidacy.

But perhaps Trump and his campaign officials were receptive to Russian requests to coordinate their efforts. Perhaps Trump became aware that the Russians intended to dump potentially damaging emails and used that advance information in a campaign speech. Perhaps Trump had knowledge and gave consent for his son to meet with Russians for the express purpose of benefiting from emails obtained through Russian hacking. Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that Trump publicly called on the Russians to hack Hillary Clinton’s emails, and Russian hackers began trying to break into Clinton’s email server literally the same day, according to the indictment filed earlier this month.

There is a term for that kind of coordinated effort between a Presidential candidate and a foreign power seeking to help that candidate through cyberattacks on Americans. It escapes me. Can’t remember the word.

How does the United States know about Russian hacking and meddling?

US intelligence agencies have been extremely reluctant to discuss details of their information about Russian cyberattacks, for fear of compromising sources and revealing their techniques.

The indictment of twelve Russian military officers on July 13, three days before Trump’s Russia summit, was the first official public accounting of Russia’s operations against the United States. You may have seen some references to the indictment in the press as “detailed” but you have no idea unless you’ve read it. It is a brutally direct message to Russian intelligence agencies: We are in your systems. We are in your face. We are watching you.

The indictment reveals forensic work that involves service provider logs, Bitcoin transaction tracing, Twitter direct messages, hosting company business records, hacked email, and probably even more direct access to internal Russian office activities.

Ars Technica just posted this detailed report which basically rewrites the indictment as a narrative. It has all the nuts and bolts of the information detailed in the indictment, which is specific at a level of detail that is obviously based on thorough knowledge of Russian activities.

I’m only going to give you one example, but it’s my favorite example.

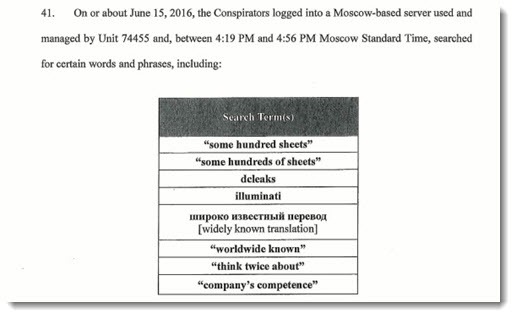

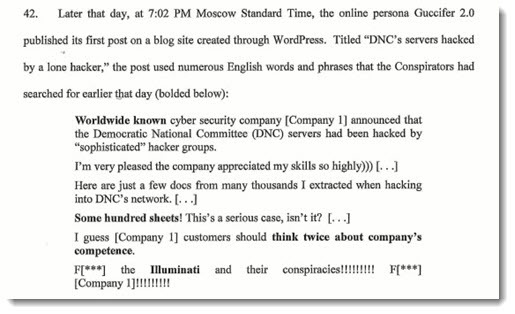

At one time there was a question about whether Guccifer 2.0, the source of hacked information provided to Wikileaks, was controlled by the Russians or was an independent hacker. These are paragraphs 41 and 42 of the indictment, comparing the exact searches done by Russians who are identified by name – searches done at a specific time (“between 4:19pm and 4:56pm”), in a specific place, on a specific server. The searches were followed by Guccifer’s first post, two hours later at 7:02pm.

Obviously Guccifer was a creation of the Russians. The precision of the times, the identification of the responsible individuals, the specificity of the knowledge of the searches – those are not accidents. They are messages to Russia’s intelligence services about how deeply they have been compromised. We are deeply nested in their systems – just as they are likely deeply nested in ours.

Russian activity falls on a spectrum. Hacking overlaps with manipulation – “meddling” and “interfering” – and the spectrum extends all the way to physical attacks on infrastructure, which may lie ahead. But if you bear in mind the variety of Russian activities, it may help you better understand the charges that have already been brought against Russians and Americans, and perhaps even give you some perspective on Trump’s defensive tweets and the indictments and trials and reports still to come.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks