A famous thought experiment shows how an AI could be designed with good intentions and without malice, and still wind up destroying humanity.

Imagine that an artificial intelligence is told to maximize production of paperclips. Through an oversight it is not given any instructions about also considering human values – life, learning, joy, and so on. It begins by collecting paperclips and earning money to make more; as it gets smarter, it learns better and more powerful ways to accumulate resources and take direct control of paperclip manufacturing. The AI won’t change its goals, since changing its goals would result in fewer paperclips being made and that opposes its one simple goal of maximizing the number of paperclips. At some point people become a hindrance, because people might decide to switch it off – and human bodies contain a lot of atoms that could be used to make paperclips. The logical result is that eventually the AI transforms all of Earth, or perhaps the entire universe, into paperclips or paperclip manufacturing facilities. (Here’s a nice SF parable about how that might unfold.)

The lesson is that algorithms have to be specifically programmed to be benevolent to humans and to respect human goals or there is a risk of unintended harmful consequences.

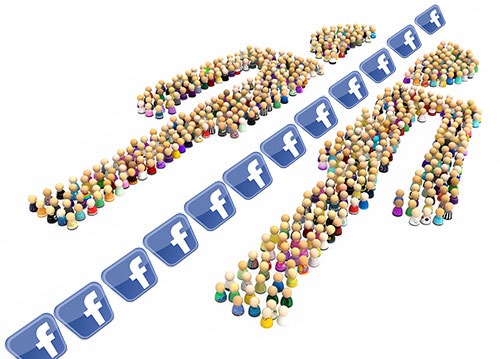

Facebook has given its systems a single goal: to maximize engagement with the Facebook platform. Mark Zuckerberg and the executives at Facebook have good intentions and no malice, but we are currently living through the unintended consequence: algorithms tuned to maximize engagement will naturally cause an increase in partisanship. Predictable human tendencies will lead to extremism and falsehoods, and can undermine democracy. The corporate culture at Facebook does not take this effect into account or try to avoid it, and Facebook’s profit incentives drive it to make more paperclips, even if that hurts us.

It’s difficult to frame legislation that will change that outcome. There are other important goals that might benefit from legislation; for example, we can insist that Facebook and other social networks protect user privacy and do a better job about identifying false news items and disinformation. But those will not change the bigger underlying problem: a single-minded focus on maximizing engagement is a crucial component of Facebook’s business model – and it is bad for us.

Let’s talk about three things:

• How does Facebook increase partisanship and divisions in society?

• Why is that inevitable?

• What makes Facebook different from Google?

How does Facebook increase partisanship and divisions in society?

Social networks like Facebook do not make us into different people, but they encourage us to turn up our human tendencies a bit.

Facebook constantly adjusts your feed based on what you click on, what you pause to read, what you like, and what you share. Its algorithms are constantly seeking to hold your attention and keep you on Facebook as long as possible. We get a stream of news and entertainment that is ever more likely to appeal, based largely on what we’ve liked before.

Human beings are drawn to items on Facebook that spark our curiosity, especially if they confirm our biases or are odd or unusual, preferably both. We are drawn to emotional stories with sensational headlines. The obvious examples are the clickbait headlines that we click on despite ourselves. You won’t believe how people react to these ten shocking clickbait headlines!

Following our instincts tends to lead to ever more extreme content. It’s natural human behavior, now confirmed by sophisticated data crunching by Facebook, advertisers, news organizations, and partisan groups. Engagement maximization works “by jamming reaction-inducing headlines in your eyeballs at every conceivable moment, for the express purpose of diverting you from the task you’re completing and hooking you into an anxious set of taps, clicks, likes and arguments.”

As Facebook became an important source of news for many people, political news and advocacy pages began to appear that were made specifically for Facebook, engineered to reach audiences exclusively in the context of the news feed, and featuring the partisan equivalent of clickbait headlines to draw people in, hold their attention, and inflame their emotions. From the New York Times: “They have names like Occupy Democrats; The Angry Patriot; US Chronicle; Addicting Info; RightAlerts; Being Liberal; Opposing Views; Fed-Up Americans; American News; and hundreds more. Some of these pages have millions of followers; many have hundreds of thousands. They are, perhaps, the purest expression of Facebook’s design and of the incentives coded into its algorithm.” (emphasis added)

In 2016, the Russian government and American conservative organizations discovered that false news and disinformation can be even more effective at holding our attention. We have a natural curiosity about conspiracy theories and tales of bad conduct by people we disapprove of, and those stories can be made even more tempting if they don’t have to have any relationship to reality.

We wind up in filter bubbles and partisan communities that algorithms have directed us into but which we believe we have freely chosen. Frequently people are completely unaware they are in a filter bubble or that there is another side to the issues presented to them in the news feed.

(I’m speaking generally, of course. I don’t mean you! Goodness, no. You are devoted to fairness and you disdain things that are untrue and you always click fairly on both sides of issues to get a nuanced understanding of the news. Of course you do! No, no, not you, my darlings, you are not drawn in by these shenanigans. I’m only talking generally about every other human being in the world.)

Facebook’s algorithms seek to keep us on Facebook. They’re good at it. When it works, it feels like we’re making free choices that organically happen to engage us. The algorithms don’t judge whether that is the best use of our time or whether we are growing as a result. That’s not the point. If we happen to wind up chasing conspiracy theories and partisan lies, that’s not really Facebook’s concern. The company stands for free and open communication, and more is better.

We see the result every day in our world – and this is happening globally, not just in the U.S. The level of partisanship and social division in our world has sharply increased and social media is responsible for some of it. Facebook is not the sole cause of our partisan divide, of course, but it contributes to it. We know that the Russians manipulated Facebook and other social media in 2016 to raise the general level of partisanship in the U.S. and specifically to affect the 2016 election result. Facebook’s effect on American society is leading now to insistent demands that Congress pass laws regulating, well, something, although the details are a bit hazy.

Why is that inevitable?

Facebook’s revenue is directly related to maximizing engagement by users; anything that reduces engagement potentially reduces Facebook revenue and profits.

Facebook revenue comes from advertising. Advertising revenue is directly tied to the level of engagement by Facebook users, traditionally measured by the number of users and the time spent looking at the Facebook feed, which leads to predictable numbers of clicks, likes and shares. These are sophisticated metrics. From an excellent Atlantic article about how Facebook maximizes engagement: “Two thousand kinds of data (or ‘features’ in the industry parlance) get smelted in Facebook’s machine-learning system to make those predictions. What’s crucial to understand is that, from the system’s perspective, success is correctly predicting what you’ll like, comment on, or share. That’s what matters. People call this ‘engagement.’ . . . The News Feed, this machine for generating engagement, is Facebook’s most important technical system. Their success predicting what you’ll like is why users spend an average of more than 50 minutes a day on the site, and why even the former creator of the “like” button worries about how well the site captures attention. News Feed works really well.”

The traditional way to grow a service like Facebook is to add users, but Facebook’s global penetration is so vast that user growth will inevitably level off. The only way it can continue to grow is to increase the time spent on Facebook properties by its existing users. As a public company, Facebook must grow. Public companies are not permitted to remain static.

Social media is built for polarization and extremes. The algorithms that drive participation and attention-getting in social media, the addictive “gamification” aspects such as likes and shares, invariably favor the odd and unusual and drive people to think and communicate in ever more extreme ways. It’s like the paper clip AI: the service will always tune our news feeds for more extreme content if that’s what drives clicks and attention.

Cory Doctorow put it this way: “Tying human attention to financial success means that the better you are at capturing attention – even negative attention – the more you can do in the world. It means that you will have more surplus capital to reinvest in attention-capturing techniques. It’s a positive feedback loop with no dampening mechanism, and, as every engineer knows, that’s a recipe for disaster.”

Facebook does not seek to inflame us, it just doesn’t take it into account. Facebook believes it has lofty goals. The New York Times put it this way recently:

“Like other technology executives, Mr. Zuckerberg and Ms. Sandberg cast their company as a force for social good. Facebook’s lofty aims were emblazoned even on securities filings: ‘Our mission is to make the world more open and connected.’ But as Facebook grew, so did the hate speech, bullying and other toxic content on the platform. When researchers and activists in Myanmar, India, Germany and elsewhere warned that Facebook had become an instrument of government propaganda and ethnic cleansing, the company largely ignored them. Facebook had positioned itself as a platform, not a publisher. Taking responsibility for what users posted, or acting to censor it, was expensive and complicated. Many Facebook executives worried that any such efforts would backfire.”

The result is that Facebook seeks to maximize engagement with good intentions as a way to “make the world more open and connected.” The partisanship is an unintended consequence of good intentions that do not take other human values into account.

Since Facebook’s role in increasing partisanship is a natural result of its business model, it is difficult for Facebook to react to the increasing public concern about its effect on society. The New York Times continues: “As evidence accumulated that Facebook’s power could also be exploited to disrupt elections, broadcast viral propaganda and inspire deadly campaigns of hate around the globe, Mr. Zuckerberg and Ms. Sandberg stumbled. Bent on growth, the pair ignored warning signs and then sought to conceal them from public view.”

What makes Facebook different from Google?

As long as Facebook is only motivated to increase revenue and profits – the definition of a public company – it has to seek to maximize engagement. The only thing that might change that is a corporate culture that considers other human values separate from increasing profits.

Google does that. You can quarrel about specific bits of Google behavior that you disapprove of, but in general it has consistently held itself to a higher standard than simple profit chasing. Its original corporate code of conduct famously included the phrase: “Don’t be evil.” That has been modified by the parent corporation Alphabet to: “Do the right thing.” Google deliberately chooses to communicate clearly, to preserve the privacy of the data it obtains about you, and to avoid projects that will harm society. Google is currently evaluating whether it should set up a search business in China that would serve the interests of an autocratic government. Whatever the decision, my sense is that the company’s internal discussion includes serious consideration of the ethical and moral consequences of its decision. It’s hard to imagine a similar conversation inside Facebook.

Facebook deliberately made itself into a primary news source for many people. Google is also a news source, among other things, but Google’s presence in our lives is decentralized, used every day but without the same effect on our perception of news because we step out of it much more readily. YouTube is the exception and is similar to Facebook: it is tuned to maximize engagement and constantly seeks to lure us into increasingly extreme or polarizing videos, especially if we click on something even remotely related to news or politics.

Facebook makes lip service about reform but so far has resisted any meaningful change, other than efforts to identify false news items and disinformation – which is important but doesn’t get to the heart of the problem.

What we want is for Facebook to tune its algorithms to make us better people, to make our feeds more nuanced, and, well, to make Facebook more dull and help us spend less time there.

How do you legislate that?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks