Forget what you know about hacking. Nation-state hackers work at an entirely different level.

Imagine that you get hacked – the bad guys get the password to your mailbox, say. The next step for most hacking attacks is that the bad guys do something that you will notice if you are watching carefully.

They might scramble your files and put a big ransomware notice on your screen. Maybe they send out spam email from your account to a million of your closest friends – you’ll hear about it pretty quickly, the bad guys are just trying to pick up some scraps before you catch on. Perhaps they send a wire transfer request to your customer, hoping the customer doesn’t pick up the phone to check with you.

You get the idea. Bad guys who hack into your mailbox might do something subtle but they’re not invisible.

Now step up to the big leagues – a nation-state seeking to plant digital bombs in highly secured government networks and the most security-obsessed large companies in the world.

The first rule for hackers in the big league is that they must be invisible. If any unusual activity is spotted, anything at all, it’s game over. The door will be closed and they’ll have to start over.

Big companies and national government agencies take security seriously. They have set up elaborate systems to help them spot anything unusual. Imagine circling your campsite with exquisitely sensitive wires and sensors to alert you to any movement. The tiniest twitch sets off an alarm that gets investigated. That’s what security is like for federal agencies and large companies, monitoring hundreds of different types of activity in the network looking for something out of the ordinary, and turning on flashing red lights and blaring sirens for any anomaly.

Actually I’m not sure about the red lights and sirens. That might have been a Mission Impossible movie. But it’s some nerdly engineering version of that, anyway.

If a hacker gets an administrator password into the network of a single company – a power grid operator, a hospital, a government agency – that’s a victory for the hacker. Celebration time, balloons, cupcakes. I think that’s what hacker parties are like. I don’t go to many parties.

But the mythical goal, the golden rings, the championship trophy is reserved for a hack that gets the hacker into multiple networks with administrative access to each one. Practically unimaginable, until the Russians proved it was possible by doing it.

That’s how we get to Solarwinds.

Solarwinds and supply-chain attacks

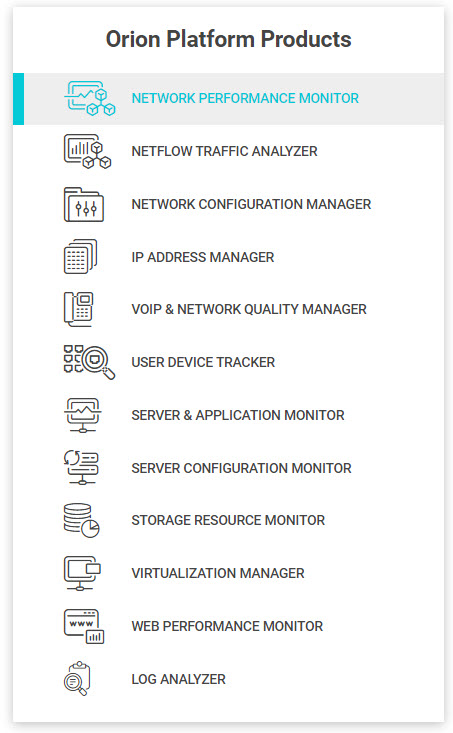

Solarwinds provides tools for monitoring and managing databases and networks. It is the dominant company in the US for enterprise network management. 425 of the Fortune 500 companies use the Solarwinds Orion platform to monitor network performance – looking for anomalies in network traffic, keeping an eye on devices connected to the network by users, and analyzing the innumerable logs kept by a modern network.

This is familiar territory. Every computer and network is monitored. Even on individual computers, Windows has built-in behind-the-scenes programs to track performance, scanning continuously for viruses, checking your hard drive for errors, and keeping logs of system events and crashes.

In your business, whether you rely on an IT consultant or have in-house IT staff, your computers are probably monitored by programs from third parties like Microsoft, Solarwinds, Kaseya, or many others. The agents keep an eye on dozens of system services, they install updates, and they likely provide remote access if you need help. Many Bruceb Consulting clients have a program that I’ve installed – look in Control Panel for “Advanced Network Management.”

Here’s a point that’s obvious when you think about it: monitoring and management agents need administrator privileges to do their jobs. They have to be able to read logs, install patches and security updates, manage services, restart computers and servers, repair databases, and a thousand more management chores.

Solarwinds is the best-known company for network monitoring and management but there are dozens of others. We can’t run our networks and stay safe without them.

So we don’t have any choice. We have to trust the network monitoring companies to stay secure.

Since monitoring and management agents from third parties are used in many networks, it’s long been well understood that a supply chain attack – malware delivered thru the third-party supply chain to multiple networks – is potentially the most destructive hack of all. A 2018 report from the Government Accountability Office recommended that agencies take the supply chain threat more seriously.

Supply chain attacks require significant resources and sometimes years to execute. The intrusion into a company like Solarwinds has to be done with complete stealth, using hacking tools that are likely only available to a nation-state. Evidence in the SolarWinds attack points to the Russian intelligence agency known as the S.V.R., whose tradecraft is among the most advanced in the world.

Cautiously, invisibly, the Russian hackers made their way into the Solarwinds network and planted malware in legitimate updates to SolarWinds’ Orion network management software. According to Solarwinds SEC filing, the malware was present from March to June 2020, long enough for all Solarwinds customers to get the automatic updates containing the malware.

In that way, 18,000 public and private sector customers downloaded a corrupted version of the Solarwinds software, which included a hidden back door that gave hackers access to each victim’s network. The unsuspecting customers include most unclassified federal government networks, major corporations, the electric grid, laboratories working on next-generation nuclear weapons, and more.

We’re still trying to figure out what the Russians did during the six months after they gained entry to the corporate and government networks. One likely possibility is that the Russians focused only on high-value targets, a few hundred networks, out of an exaggerated desire to remain invisible and not set off any alarms. In those targets, the Russians almost certainly removed any evidence of the Solarwinds entry point, covering their tracks by erasing log entries and removing no-longer-needed files, and setting up new methods of persistent access – the ability to infiltrate and control networks in a way that is difficult to locate or remove.

We’ll talk later about who was hacked and what the Russians might have planted on the networks. Before we get to that, in the next article we’ll look into another interesting question: Should we blame Solarwinds?