Ransomware is big business. I mean that in the most boring way possible.

Have you been following the news about the Colonial Pipeline hack? There is a nuance that sheds much light on the modern world, but to get to it I need to be sure you have the basic facts of what happened last week.

True facts about the Colonial Pipeline hack

Colonial Pipeline operates one of the largest oil pipelines in the US, supplying the east coast with nearly half of its gasoline and jet fuel over a pipeline network extending 5500 miles.

Colonial Pipeline has two computer networks: one for the business, a separate one for the infrastructure controlling the pipelines and equipment.

The business network was infiltrated by hackers who encrypted all the company files with ransomware, making the network inoperable, then demanded millions of dollars to decrypt the files along with a promise not to attack the company again if the ransom was paid.

The ransomware attack was aimed at the business network, but Colonial Pipeline took the pipeline offline as a precaution because it didn’t know if the attackers might also have infiltrated those computers. It pays to be cautious when you are in the business of moving millions of gallons of liquid that blows up and goes boom. The shutdown disrupted the flow of heating oil, gasoline, and jet fuel on the east coast for several days.

There was much excitement. Government agencies, law enforcement spokespeople, journalists, bloggers, Twitter, and the Kardashians weighed in with conflicting advice: Don’t pay! Hoard gasoline! Get a grip! Few people advised the company publicly to pay the ransom but in the real world it was the obvious way out of their dilemma.

Colonial Pipeline eventually decided to pay five million dollars to decrypt its files and avoid having its corporate secrets posted publicly. Pipelines are back in full operation. President Biden signed an executive order to improve cybersecurity.

Darkside and the big business of ransomware

Darkside is a hacking group based in Russia. It is not believed to have direct ties to the Russian government. (The picture above is not their logo, it just looks cool.)

The attack against Colonial Pipeline is blamed on Darkside but that’s not technically true. It was actually carried out by a Darkside customer or affiliate. How do we know that? Because that’s what Darkside said in a press release on the Darkside website.

Now stop for a minute and think about those words: “a press release on the Darkside website.” Try and make that fit in your mind alongside “Russian hackers who brought down a big company with a ransomware attack.” They don’t really go together, do they? That’s the interesting part of this whole episode.

Darkside is a profitable company launched with a press release in August 2020. It is likely a spinoff from another group, REvil, another ransomware-as-a-service company believed to be responsible for extorting more than two billion dollars from its targets.

Its business is providing software to hack large companies and customer support for hackers using the Darkside programs. Darkside customers have to do their own work to gain access to a company network. Once they’re in, then they can buy an off-the-shelf ransomware package from Darkside and start the process of encrypting files and demanding millions of dollars. Remember going to Office Depot and buying Quickbooks in a box? Ransomware is kind of like that now.

Darkside provides IT support and add-on services, like tools to allow hackers to communicate directly with their targets and launch DDoS attacks on websites of victims unwilling to pay. Darkside claims in its advertising on the dark web that its encryption software is faster than the competitors. It supports attacks on Windows and Linux-based networks.

Part of Darkside’s business model is based on its public profile. It does not hide in the shadows. A ransomware attack today starts with encrypting a company’s files so its network is unusable. The ransom pays for a decryption key that can be used to restore the files; it’s faster and cheaper than restoring from a backup, which is a difficult process fraught with error. It sounds curious but Darkside’s reputation is part of the reason to pay the ransom; it has a history of dealing, well, honestly with its victims and supplying the key instead of disappearing with the money.

But there’s another element to running a ransomware company out in the open. Today’s ransomware attacks are a two-pronged threat. Before encrypting the company’s files, the hackers download data from the company network, then threaten to release it publicly if the company does not pay the ransom. The big ransomware companies have become skilled at media manipulation to do maximum damage with compromising or damaging data dumps. Forbes reported this about another high-profile ransomware group named Babuk:

Another group, Babuk, has shown in the past month how devastating public shaming can be, after it hacked into the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Police Department. When the police didn’t pay the $4 million ransom, Babuk started releasing the personal information of officers. In a new batch of data on 22 police officers released this week, the leaked information included psychological assessments, social security numbers, financial data and marriage histories. Babuk even posted conversations between itself and the department, in which the latter apparently tried to lowball the crew with a $100,000 ransom offer.

The websites for Darkside and companies like them (thirty or more companies are in the ransomware business) are used to promote the companies’ services and attract media attention for their successful hacks. More from Forbes:

DarkSide has used a different tactic to try to improve its public image, presenting itself as a kind of Robinhood hacking organization, giving a small portion of stolen funds to charity, offering short-sellers advance information so they can bet on a victim’s stock tanking, and promising not to attack certain industries: hospitals, funeral services, schools, universities, nonprofits and government organizations. It even claims to only permit attacks on companies it knows can afford to pay, saying, “We do not want to kill your business.” As the group wrote on its dark web “press center” earlier this week: “Our goal is to make money, and not creating [sic] problems for society.”

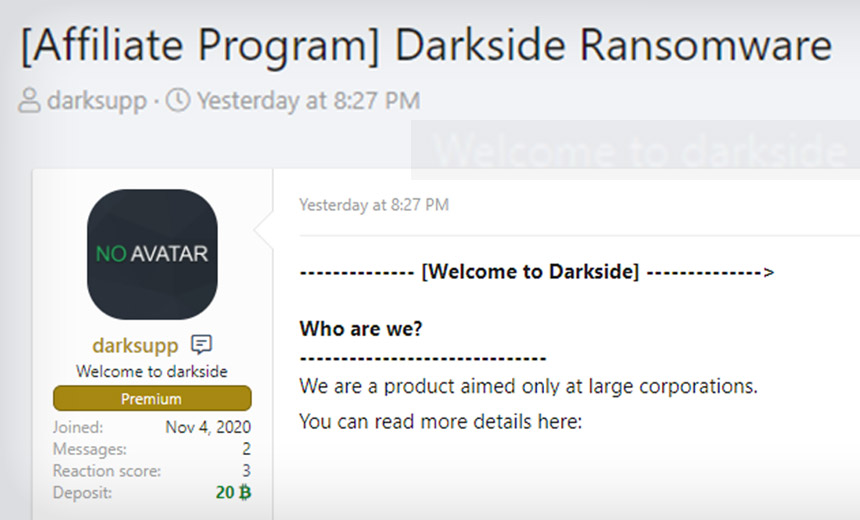

Late last year Darkside launched an affiliate program. An affiliate program!

Darkside and other ransomware companies attack big companies that have an interest in keeping things private to protect their reputation. Pick a ransom amount that the company can afford to pay, negotiate the final payment, then split the proceeds with Darkside. According to security company Fireeye, Darkside takes 25% of ransom fees less than $500,000, decreasing to 10% of ransom fees above $5 million.

Ransomware has exploded in recent years because cryptocurrencies make payments harder to trace. More large companies have cyberinsurance to pay the ransoms, which all too frequently gives companies an excuse to procrastinate on improving their security, a difficult and expensive challenge.

Darkside ransomware has been identified in a steadily increasing number of attacks in 2021, mostly in the US – ten, fifteen, twenty attacks a month, across multiple sectors, including financial services, legal, manufacturing, professional services, retail, and technology. Ransomware-as-a-service is a growth business. Darkside and the other ransomware companies are becoming very rich.

But Darkside ran into a problem last week: the attack on Colonial Pipeline was too successful.

Why it was a problem that the Colonial Pipelines hack was too successful

Here’s a thought experiment. Imagine that a company provides services to people who kidnap children. Kidnappers can buy a package that handles renting an apartment for the child during ransom negotiations, takes care of details for child care and meals, and helps the kidnappers communicate securely with the police and parents. Valuable service for first-time kidnappers, right?

The company providing Kidnapping-As-A-Service asks for one thing from its customers: kidnap children of rich people but not TOO rich or well-known.

A customer buys the Kidnap Platinum package and kidnaps its first child. In their zeal, they choose poorly and kidnap, I don’t know, I’m making this up, does Jeff Bezos have children? Let’s say Jeff Bezos has a ten-year-old child that gets kidnapped.

Bezos goes berserk and hires Liam Neeson to handle the negotiations. The world erupts with anger. The US government mobilizes to bring everyone involved to justice. The public reaction is brutally negative toward the kidnappers and even worse for the company that facilitated the kidnapping.

That’s Darkside’s dilemma. They say – and it sounds quite believable – that they were not expecting to shut down the oil pipeline and disrupt the entire US east coast. They just wanted to run a nice quiet ransomware operation, collect a few million dollars, and move on, as they have done many times before.

This attack blew up and got way too much attention. From the New York Times: “There was some evidence, even in the group’s own statements on Monday, that suggested the group had intended simply to extort money from the company, and was surprised that it ended up cutting off the main gasoline and jet fuel supplies for the Eastern Seaboard.”

Everybody hates Darkside and wants to bring them down. As of a couple of days ago, it appears the company has shut down under the pressure (or possibly from government disruption behind the scenes). Its website on the dark web disappeared, it lost access to its payment processing system, and it closed its affiliate program.

How do we know that? The company issued a press release.

The lesson I want you to carry away: the Colonial Pipelines hack is business as usual. Ransomware is a threat faced by large companies all over the world – and already being handled routinely by more companies than you realize. Targeted ransomware attacks are being carried out by companies with press centers and affiliate programs and who knows, maybe pension plans.

Security is difficult. It’s expensive. There is no obvious reward for taking on the burden of being secure – not for big companies paying experts to make their networks more difficult to access; not for us as we fumble with two-factor authentication. The reward is intangible: our lives and our businesses proceed quietly without interference. The world is a dangerous place. Be careful out there!