Breaking news: Artificial intelligence is going to reshape the legal industry again, for the first time.

Way back in 2011, the New York Times looked at the advent of e-discovery software and declared in its headline, “Armies of Expensive Lawyers, Replaced by Cheaper Software.” The article refers to “artificial intelligence” but I don’t think those words meant what they thought they meant.

The headline didn’t age well. It’s true that clever programs took over some of the laborious aspects of legal work. Associates diving into discovery repositories with millions of documents could use keywords and metadata to find needles in haystacks.

But employment in the legal profession has grown faster than the American workforce as a whole. Software in the 2010s was an aid for lawyers, not a replacement.

Now there’s a hue and cry about the legal profession again because the technology driving AI has the potential to be far more disruptive. The fundamental legal skills are reading, analyzing, and summarizing. Those happen to be exactly the things that AI handles as well as (or better than) humans. And AI does its work faster and cheaper than people, and likely does it more accurately and thoroughly.

You might be skeptical and think the fuss about AI taking over lawyers’ jobs is overstated. After all, you’ve heard anecdotes about lawyers using AI to write briefs and being embarrassed by case citations that were fabricated by a hallucinating AI. (Here’s one in 2023, and another in 2024 and last month in a PI case against Walmart.) If you’re an AI skeptic, you see stories like that and feel smug – obviously AI can’t be trusted and the bubble will burst soon.

Yeah, not so much. Be careful of confirmation bias – seizing anecdotes that match what you want to believe and missing the big picture. This should be your guidepost for AI in 2025:

When you use AI and get an unsatisfying result, do not conclude that AI is a failure.

Instead, ask yourself, “How long will it be before this problem is solved?”

Then cut your time estimate in half.

It will likely be sooner than that.

Want some predictions from smart people?

A study by researchers at Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania, and New York University concluded that “legal services” was the industry most exposed to new AI. Another report by economists at Goldman Sachs estimated that 44 percent of legal work could be automated by generative AI. Forrester, a market research group, predicted that almost 80 percent of jobs in the legal sector would be significantly reshaped by AI technology.

Yet the Bureau Of Labor Statistics thinks legal job growth will continue to be faster than overall employment. Students certainly hope so – law school applications are running 20% higher in 2025 than last year.

Most lawyers testing AI today agree that it can already write a legal memo as well as a first year associate. That means those new hires will not provide any value if their skills are in memorization and information recall. Ben Allgrove, a partner at international law firm Baker McKenzie, put it this way:

“The impact, Mr. Allgrove said, will be to force everyone in the profession, from paralegals to $1,000-an-hour partners, to move up the skills ladder to stay ahead of the technology. The work of humans, he said, will increasingly be to focus on developing industry expertise, exercising judgment in complex legal matters, and offering strategic guidance and building trusted relationships with clients.”

The legal culture is conservative. The higher productivity from AI tools means fewer billable hours, increasing the pressure on law firms to bill for work done rather than time spent. But law firms and corporate clients are loath to challenge traditions; that kind of change to client relationships will come slowly.

AI tools for lawyers from Thomson Reuters

Everyone involved in AI development is in a hurry.

Giant tech companies are pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into research and infrastructure for the basic AI models that will underlie all the big changes ahead. AI tools have the potential to disrupt every job that uses language and communication – which is to say, almost every job in every industry and profession.

Thomson Reuters is a monolithic force in the legal industry. It is spending hundreds of millions of dollars on development of AI tools to enhance or replace its vast array of existing legal software. It has unique proprietary resources and entrenched relationships but it still wants to be first – just as Microsoft is racing to build reliable enterprise tools to preserve its dominant position in large businesses.

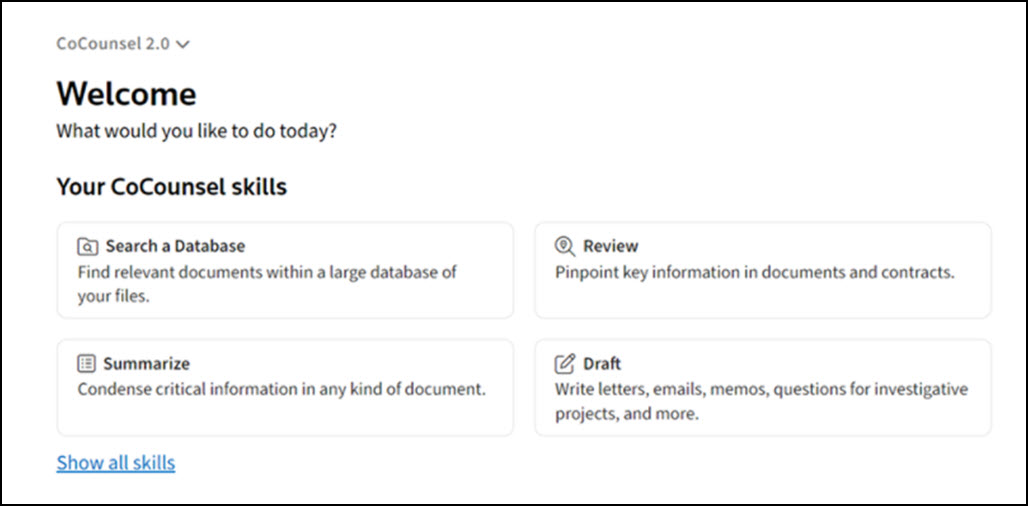

CoCounsel is at the heart of its AI tools. It’s a generative AI assistant acting as a platform with features for research, document review, and drafting. It integrates with some of the multitude of other AI tools offered or planned by Thomson Reuters.

Thomson Reuters is building AI into research tools like Westlaw and Lexis+. There is a dizzying array of names for different niches – Westlaw Precision (legal research, AI suggestions for legal claims that are relevant to facts of a case, jurisdictional surveys); Westlaw Edge (predictive research suggestions, litigation analytics, a tool to identify gaps in legal documents); and more, much much more.

And new startups are jostling with established software vendors in the legal profession to take the market away from Thomson Reuters. Harvey is making a splash for analyzing complex litigation scenarios. Clearwell is designed to handle analysis of large volumes of documents in discovery. There are literally thousands more companies working on bringing AI-driven tools to lawyers.

The AI rollout in the legal profession, like other professions, will have four aspects.

Fine-tuning for legal tasks The giant tech companies are training AIs like ChatGPT and Microsoft CoPilot on vast amounts of general text data. Thomson Reuters and other law software vendors will fine-tune these models using legal-specific data, such as case law, statutes, regulations, and legal documents. Thomson Reuters has an advantage because of its huge library of proprietary and trusted legal content.

Development of legal-specific features Thomson Reuters is working on development of features tailored to the needs of legal professionals. It will produce tools for drafting legal documents, conducting legal research, summarizing case documents, analyzing contracts, and generating deposition questions.

Implementation of guardrails and quality control Any company producing AI software for the legal profession will be focused on eliminating hallucinations and made up cases. The reputation of Thomson Reuters will rest on its mechanisms to improve accuracy and reliability. A crucial feature will be “prompting guardrails” that restrict the AI’s responses to verified information, as well as features that allow lawyers to easily verify the sources of the AI’s output.

Focus on security and confidentiality The proprietary layer added by Thomson Reuters and other vendors will incorporate security measures and protocols to protect sensitive client data and ensure that customer data is not used to train the underlying AI models.

Jobs will be lost and gained, the old guard will resist, there will be anecdotes about mistakes and bugs, product names will blur and change – and productivity will go up.

This is what disruption looks like while it’s happening.