On July 18, 1874, Lewis Carroll was on a morning walk when a sentence popped into his head: “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.”

That thought led to one of the greatest works of English literature that you’ve never heard of.

It had been ten years since Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland had been published to worldwide acclaim, and three years since Through The Looking Glass, And What Alice Found There was embraced as a worthy sequel. The two books were immediately hailed as children’s classics, found in every library, reprinted frequently, read aloud to children everywhere.

Lewis Carroll (pen name for Charles Dodgson, you knew that, right?) was an English author, poet, mathematician, photographer and reluctant Anglican deacon. During his life he wrote weekly magazine puzzles, was a well-known photographer, invented games and odd devices, and wrote a dozen mathematical books.

It was always the Alice books that made him a celebrity. But there was one more creation that stands proudly with the Alice books for Carroll scholars and collectors – and for fans of a certain type of very odd, twisty writing style.

Carroll returned from that morning walk convinced that he had been given the last line of an epic poem. He had embedded a short poem, Jabberwocky, in Through The Looking Glass, but his instinct was that the Snark line would be the conclusion of a full-length work.

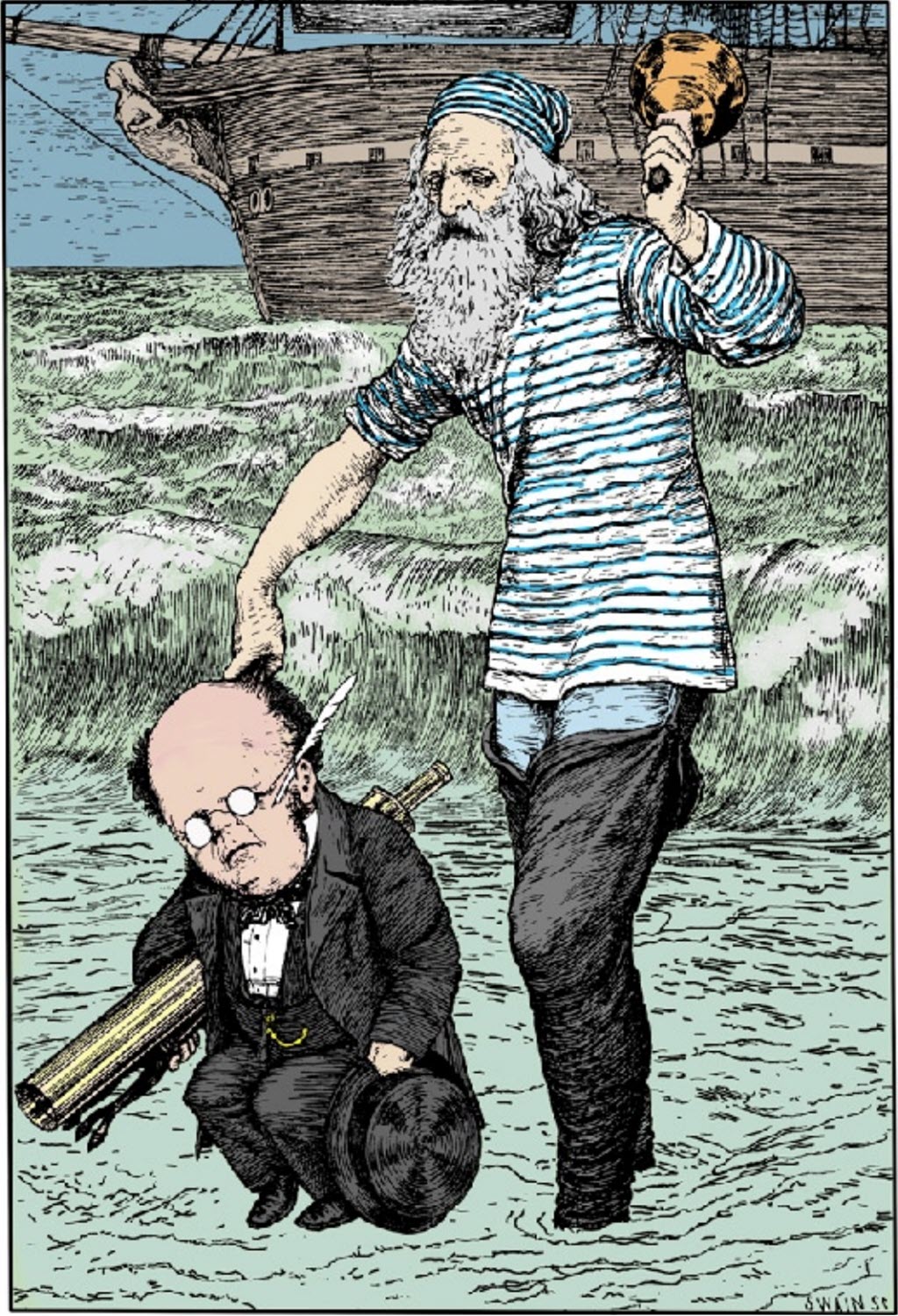

Over the next eighteen months, Carroll wrote 141 stanzas of The Hunting Of The Snark: An Agony, In Eight Fits. It tells the story of an adventuring crew that sails to an island that is “just the place for a snark!” The leader of the group is the Bellman; the crew includes the Baker, the Banker, the Barrister, the Billiard-Marker, the Broker, the Maker of Bonnets and Hoods, the Boots, the Butcher and the Beaver. (It is an actual beaver, albeit one that is shy and likes to make lace.)

A true Snark, says the Bellman, tastes crispy when cooked, gets up late in the morning, can’t take a joke, is ambitious and has a “fondness for bathing-machines/ Which it constantly carries about,/ And believes that they add to the beauty of scenes —/ A sentiment open to doubt.” Some Snarks, we’re also told, have feathers and bite; others have whiskers and scratch. You might also occasionally encounter one that is a Boojum.

In other words, The Hunting Of The Snark is a nonsense poem, of a type that is seldom done well and these days rarely attempted at all. Shel Silverstein is probably the best known author of nonsense poems in the 20th century. There have been few worth remembering in the last fifty years.

Carroll’s “Snark,” by the way, has no connection to the contemporary use of the word “snark,” defined as “the way Bruce writes about Microsoft.”

When you read The Hunting of the Snark, you may feel like Alice when she heard Jabberwocky: “Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas — only I don’t exactly know what they are!” It is filled with mysteries and puzzles and wordplay and teasing references to the number 42. There is no evidence that the poem inspired Douglas Adams to make 42 the answer to life, the universe, and everything, but synchronicity is a wonderful thing.

The poem never describes why the group is searching for a Snark, and at Carroll’s insistence, the illustrations never include a Snark, but it is obviously fearsome. The Baker vividly remembers the parting words of his uncle:

But oh, beamish nephew, beware of the day,

If your Snark be a Boojum! For then

You will softly and suddenly vanish away,

And never be met with again!

Since then, the Baker lives in dread, unable to sleep and racked with dark premonitions. The Barrister dreams of a nightmarish trial in which a pig is defended by the Snark; the Butcher and the Beaver, hitherto enemies, grow inseparable after hearing the terrible cry of what might be a Snark; the Banker even goes insane when he is nearly carried off by a Bandersnatch.

Nonetheless, the crew’s commitment to the quest is absolute.

They sought it with thimbles, they sought it with care;

They pursued it with forks and hope;

They threatened its life with a railway-share;

They charmed it with smiles and soap.

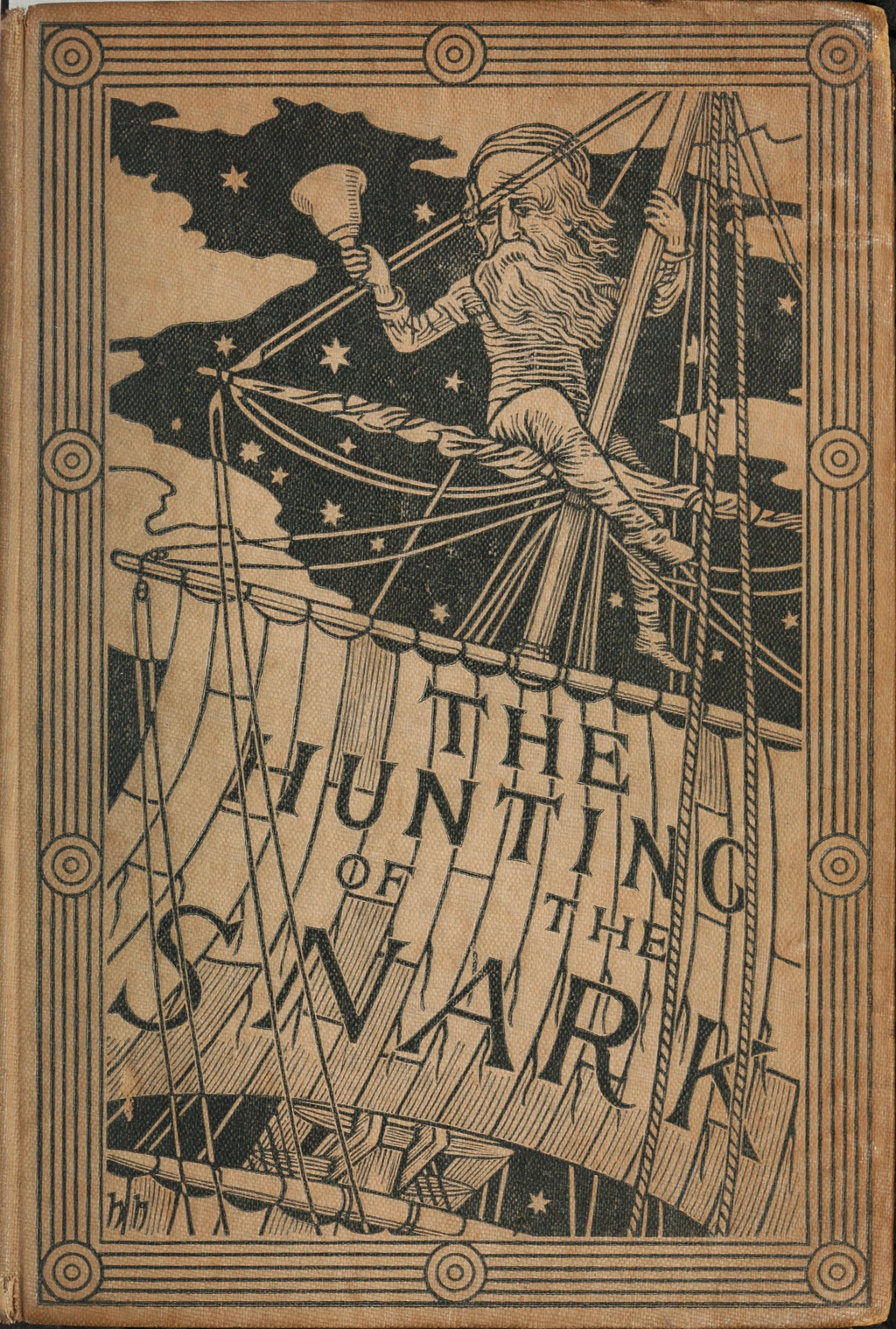

An illustrator, Henry Holiday, was engaged and after a few delays, the first edition of The Hunting Of The Snark appeared on April 1, 1876. The first printing of ten thousand copies sold out almost immediately and reprints began to appear every few months. It joined the Alice books in the public consciousness but it never became as much of a fixture on the shelf of read-aloud books for children, probably because it is so unrelentingly strange.

In the 150 years since Snark was published, there has been an endless stream of commentary and analysis. It’s an allegory for the pursuit of happiness. It’s about the inevitability of death, according to Martin Gardner. It’s an investigation of the void, say French theorists. It’s an allegory for tuberculosis, or a parody of a highly publicized English court case, or a satire of controversies between religion and science, or it was inspired by the death of Carroll’s uncle.

Or perhaps it is simply, gloriously, meaningless. When directly asked whether The Hunting of the Snark was an allegory or contained a hidden moral or political satire, Carroll’s published answer in 1887 was, “I don’t know!” Carroll wrote to a reader after the publication, “When you have read the Snark, I hope you will write me a little note and tell me how you like it, and if you can quite understand it. Some children are puzzled with it. Of course you know what a Snark is? If you do, please tell me: for I haven’t an idea what it is like.”

But The Hunting of the Snark lives on as more than a source of research papers.

It has inspired books that are direct sequels, continuations, or reimaginings. David Elliot’s Snark: Being a true history of the expedition that discovered the Snark and the Jabberwock … and its tragic aftermath is one of the most recent of these. (Jack London’s book The Cruise Of The Snark is not an adaptation of the poem but he did indeed name his ship the Snark as an homage when he sailed to Hawaii.)

There have been several adaptations of the poem into stage musicals, most recently a West End musical by Mike Batt. (The first cast recording featured Art Garfunkel as the Baker, Sir John Gielgud as the narrator, Roger Daltrey as the Barrister, and instrumental contributions from George Harrison, among others.) A film adaptation was released in 2023. There have been opera and theater adaptations. It has inspired music in various forms, including a piece for trombone by Arne Nordheim, a jazz rendition, and a French translation with music by Michel Puig. A BBC Radio adaptation with music and songs has also been broadcast. A twice-yearly journal is published by the Institute Of Snarkology.

At least one phrase has made its way into popular culture. The Bellman says:

Just the place for a Snark! I have said it twice:

That alone should encourage the crew.

Just the place for a Snark! I have said it thrice:

What I tell you three times is true.

Do you know that expression? In a conversation with the Secretary of the Navy, President Theodore Roosevelt said, “Mr. Secretary, what I tell you three times is true!” The Secretary of the Navy replied stiffly, “Mr. President, it would never for a moment have occurred to me to impugn your veracity.” President Roosevelt was familiar with the poem; the Secretary obviously was not.

At one time the idea might have been amusing – the concept of something becoming true through repetition is inherently absurd. Alas, in 2025, it has become a basic organizing principle for too many of our leaders, who repeat crazy things so many times that people believe they are true.

Sigh.

But mostly there are the books. The Hunting Of The Snark is about eighty pages when it’s printed with wide margins and illustrations.

Copyright terms in the late 1800s were complicated but the important thing to know is that they were short. The Alice books and Snark were out of copyright and being published in other editions in the blink of an eye, sometimes with the iconic original illustrations, sometimes interpreted by other artists.

That creates the perfect environment for book collectors. And my goodness, have there been collectors. I’ll tell you more about the obsessive world of Lewis Carroll collectors in the next article.