Previously:

Location Tracking: They Know Where You Are

Location Tracking: LA LA LA I DON’T WANT TO HEAR YOU

Our phones track our movements every minute of every day. We carry around beacons that continuously broadcast their location. Our phones are remarkably efficient surveillance tools.

But it’s not just our phones. There are six ways that our location is tracked.

- Facebook & Google

- Other third-party apps

- Cell tower tracking by phone carriers

- Location tracking by IOT devices, RFID tags, and Bluetooth

- License plate readers

- Cameras with facial recognition systems

Today we’ll take a look at Facebook, Google, and phone apps – the ones that we have at least some minimal control over. In the next article we’ll see where the phone carriers fit into this picture.

Facebook & Google

Facebook and Google collect data from their own apps on your phone. They say they don’t sell it but keep it for themselves to personalize their services and sell targeted ads across the internet.

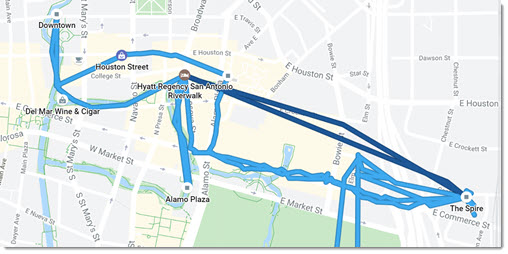

Unless you turn off tracking, Google tracks your location continuously in Google Maps and other Google apps, especially on Android phones. You can see a map of your movements – every mile, every step – by logging into Google Maps Timeline. If you’ve never done that before, it is very strange to see that timeline for the first time and realize how detailed it is, showing where you walked or drove, how long it took, where you stopped and where you shopped. The picture above shows my trail walking around San Antonio a few months ago.

I’m more at peace with Google’s tracking than anything else we’ll discuss here. Google has never sold location data to third parties or given it away. I believe that as long as Google keeps the information to itself, its data collection is not an invasion of privacy; it’s an evolution of privacy where I choose to give information to Google, and only Google, in exchange for technology that improves my life like Google Photos and Google Maps.

Facebook, though – ah, Facebook. Facebook built its business on handing out or selling data about you (including your location) to advertisers, app developers, researchers, and bad actors like Cambridge Analytica.

Today Facebook is probably not selling or giving away data about you. That’s a recent development. Facebook has been badly stung by criticism over its data sharing and now faces a hostile regulatory and political environment. Both Google and Facebook are incentivized now to keep the data they collect exclusive to their own platforms: they can claim to be protectors of your data while they sell advertising at a premium.

Unless you turn it off, the Facebook app on your phone continuously tracks your location and uses it for targeted ads. Facebook loves location data. It has applied for patents to extend its location tracking and make it more accurate. One patent, for example, uses your previous location data – and the previous location data of people you know or have been physically near — to predict your future location.

Perhaps Facebook has learned its lesson about protecting our data, but it has a long, long way to go to regain our trust.

Phone apps that track your location (whether you know it or not)

At least 75 companies receive anonymous, precise location data from apps whose users enable location services, the New York Times found.

“These companies sell, use or analyze the data to cater to advertisers, retail outlets and even hedge funds seeking insights into consumer behavior. It’s a hot market, with sales of location-targeted advertising reaching an estimated $21 billion this year.”

When an app tracks your location, the app developers can make money by directly selling their data, or by sharing it for location-based ads, which command a premium.

Apps may collect location data even though that has nothing to do with the purpose of the app. The explanations you see when an app requests permission to obtain location data are often incomplete or misleading. An app might tell you, for example, that granting access to your location will help the app get traffic information; it’s only hinted deep in the privacy policy that the data will be shared and sold. Typical example uncovered by the New York Times:

“When prompting users to grant access to their location, (TheScore, a sports app) said the data would help “recommend local teams and players that are relevant to you.” The app passed precise coordinates to 16 advertising and location companies.”

Uber needs to know your location to run its app, of course. But it came to light that Uber was tracking customers not only when they were in an Uber car but also beyond it, and then continued to track users even when the Uber app was uninstalled.

Location data from phone apps is drying up as Apple and Google offer stronger, clearer privacy controls on their platforms. You are warned more prominently when apps request location data, and a new option permits you to give an app access to data only when it is being used. The restrictions serve Google and Facebook well, since they would prefer that advertisers come to them for the most effective targeted ads. Marketers will turn to less precise methods of tracking your location, using IP addresses, for example. Fast Company says: “IP addresses are less accurate than the precise GPS coordinates that apps had been collecting previously, which means marketers will have a tougher time tracking your precise whereabouts. In practical terms, that means location-based advertising will probably get a lot dumber in the near term, as marketers lose the ability to determine what store you visited or where you had lunch.”

Apps that track students

Here’s an unexpected example of how location data is being collected and used.

Dozens of schools have started to force students to install apps on their phones that use GPS, wi-fi connections, and short-range Bluetooth sensors to track students’ locations. The Washington Post recently reported:

“One company that uses school WiFi networks to monitor movements says it gathers 6,000 location data points per student every day. School and company officials call location monitoring a powerful booster for student success: If they know more about where students are going, they argue, they can intervene before problems arise. But some schools go even further, using systems that calculate personalized “risk scores” based on factors such as whether the student is going to the library enough. School officials give SpotterEDU the students’ full schedules, and the system can email a professor or adviser automatically if a student skips class or walks in more than two minutes late.”

The founder of another student tracking app describes the benefits this way:

“By logging the time a student spends in different parts of the campus, Benz said, his team has found a way to identify signs of personal anguish: A student avoiding the cafeteria might suffer from food insecurity or an eating disorder; a student skipping class might be grievously depressed. The data isn’t conclusive, Benz said, but it can “shine a light on where people can investigate, so students don’t slip through the cracks.” “

Maybe those are real benefits that help real people. Or maybe it’s a perfect example of a nightmarish surveillance state. Most likely, it’s both, which is what makes this such a difficult issue.

In the next article we’ll look at the phone carriers and a few other ways that we are tracked everywhere we go.