If you have any illusion that privacy means anything, forget it. If you are targeted for surveillance, there is nothing you can do to prevent it. Every keystroke on your computer will be logged. Everything you do on a phone – every message, every call, everything – will be intercepted. There are no tricks that will be sufficient to let you hide.

Part of the reason has nothing to do with technology. It’s the way the world works if you are specifically chosen as a target. Leo Laporte put it this way on This Week In Tech: “When you’re walking down the street, you’re vulnerable to ninjas. If a ninja decided to take you out, what are you going to do? Nothing. The good news is, most of us are not being targeted by ninjas.”

Our technology is pretty secure against random attacks. Our operating systems are hardened. Our devices are secure. Our iPhones are encrypted. Nothing will get past you if you’re constantly paranoid and study the Rules for Computer Safety.

So how is it possible for governments or bad guys to penetrate your devices and spy on you? Interesting question. And like so many bad things these days, the answer has to do with money. Big money.

There have been several stories in the news recently that will help you understand how your devices can be used against you if you become a target.

Some of the stories feature “security researchers” who are willing to trade your security, your privacy, and even your personal safety for large amounts of money. We’ve got a security company that endangered people’s lives so they could make a profit in the stock market, and another one that sells the most dangerous kind of security vulnerabilities to the highest bidders.

And there’s a story about a hack by our government that ought to be shocking. It’s hard to be shocked in a world that contains Martin Shkreli, Theranos, and Donald Trump, but reserve a bit of outrage for the latest news about the NSA.

MedSec puts lives at risk

Computer security scientists and even many hackers observe a policy of responsible disclosure of vulnerabilities in software or devices. When a flaw is discovered, it is reported to the developers of the insecure program or device, who are given a reasonable amount of time to fix the security vulnerability and prevent any future damage. At the end of that time, the details of the flaw can be published by the developers, by the researchers who discovered the flaw, or both. Since security researchers expect to be compensated, the big technology companies – Microsoft, Google, Facebook, et al. – pay substantial bug bounties when a flaw is brought to their attention. Apple announced its long-awaited bug bounty program in early August, offering payments of up to $200,000.

It’s a crucial part of keeping our technology safe. Once a vulnerability is announced, hackers worldwide immediately try to reproduce it, hoping to exploit the flaw before it’s fixed. That’s why updates have become so important; it’s a race between the developers and the bad guys, and the developers frequently only have an edge for a short time.

Here’s an example of how that’s working in the real world.

MedSec Holdings, Inc., is a cybersecurity firm that focuses on the healthcare industry. It discovered flaws in medical devices sold by St. Jude Medical, Inc., that potentially could allow attackers to interfere with pacemakers, implantable defibrillators, and the monitoring device that communicates with them. Like other medical device manufacturers, St. Jude has an active vulnerability disclosure program.

MedSec didn’t approach St. Jude.

They called their brokers.

MedSec engaged an investment firm and shorted St. Jude’s stock. Then MedSec went public and sent press releases to everyone they could find claiming that St. Jude’s devices are life-threatening. MedSec crowed that unauthorized devices could tap into implanted devices and cause potentially fatal disruptions.

All they had to do then was sit back and watch St. Jude’s stock fall, generating profits for MedSec and the investment firm. Oh, and possibly endangering the lives of patients that depend on St. Jude pacemakers and defibrillators. They didn’t mention any of this to St. Jude quietly ahead of time – don’t be silly, there are profits to make in the stock market!

Got it? MedSec dug and dug until they uncovered methods of hacking into pacemakers. They shorted the company’s stock and made the vulnerabilities public, deliberately endangering patients to make the stock price go down so they could profit.

Information Week got a statement from Marie Moe, a pacemaker wearer and cybersecurity researcher: “As a patient I am angry, because the researchers did not seem to act in the interest of patient safety with their choice of disclosure strategy. They used fear mongering as a tactic to maximise their monetary profit. The lack of empathy is striking.”

Remember business ethics? Just a quaint nostalgic memory for us old-timers. MedSec’s actions may not have been illegal but my god, what revolting human beings!

There are good write-ups of the MedSec/St. Jude episode here and here.

NSO sells exploits to the highest bidder

Obviously the highest value security vulnerabilities are the ones that no one knows about except the attackers. If an iPhone can be hacked and Apple doesn’t find out about it, Apple can’t fix it. “Zero day exploits” allow attacks that cannot be blocked because there is no fix for them. Companies like Apple, Microsoft and Google are constantly searching worldwide to discover and fix all vulnerabilities that they find out about. Zero day exploits that stay secret are highly valued.

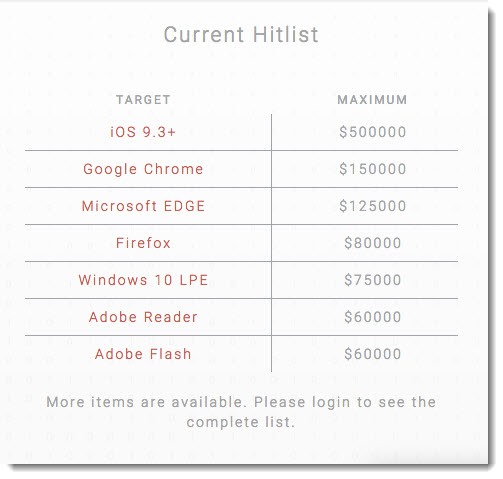

It tells you something that when Apple announced bug bounties of up to $200,000, a Texas company immediately offered more than twice as much for anyone who sold exploits to the company instead of submitting them to Apple. It calls the bug acquisition business a “research sponsorship program.”

Zero day exploits are then sold to high paying customers. That might be bad guys, sure. More often it’s governments, because these are the hacks that lets a government target a particular phone or computer as a way to gather useful intelligence. That’s the kind of thing you want our government to be doing to stop terrorism, right?

Yeah, well, about that. It turns out that the buyers are often governments with slightly less pure motives. These are the tools that are used to target journalists. Activists. Human rights defenders. Political opponents. Documents emerged last year about an Italian company – a respectable company whose executives wear suits and get big paychecks and utter pious platitudes about the purity of their business – showing that the company had sold malware to groups in Egypt, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan.

An example emerged two weeks ago about how dangerous it can be when security exploits are sold to the highest bidder. Prominent human rights activist Ahmed Mansoor, based in the United Arab Emirates, got text messages on his iPhone 6 that didn’t feel quite right. He has some experience with surveillance software so instead of clicking on the links in the messages, he turned the messages over to good guys, Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs. Citizen Lab set up a stock factory iPhone and loaded the URL in the messages. All they saw was the Safari browser opening to a blank page, then closing again.

And with that, the iPhone was completely compromised. Everything done on the phone was being transmitted invisibly to a worldwide network of servers run by . . . whoever had launched the attack.

After a huge effort, Citizen Lab was able to piece the puzzle together. According to Wired:

“An established private cyberarms dealer called NSO Group, whose clientele primarily comprises governments, has been selling masterful spyware that is delivered to mobile devices through a series of critical vulnerabilities in Apple’s iOS mobile operating system. Once established on a device, this tool, known as Pegasus, can surveil virtually anything, relaying phone calls, messages, emails, calendar data, contacts, keystrokes, audio and video feeds, and more back to whomever is controlling the attack.”

Once the vulnerabilities had been discovered, Apple was immediately able to patch iOS to fix the flaws that made the attack possible. That’s why your iPhone got an update last week.

NSO Group is a company based in Israel that is shrouded in secrecy. Its LinkedIn profile says it has between 201 and 500 employees. Bloomberg estimated its annual earnings in 2014 at $75 million. Citizen Lab reports that NSO Group appears to be owned by a venture capital firm headquartered in San Francisco, which was shopping it around last year at a valuation of $1 billion.

Only governments can afford NSO Group services, often authoritarian governments with proven records of human rights abuses and targeting of dissidents and activists. Lookout, a mobile security company that worked on cracking the malware behind the Mansoor attack, calls them “cyber arms dealers.” The New York Times describes their techniques: “In many cases the NSO Group had designed its tools to impersonate those of the Red Cross, Facebook, Federal Express, CNN, Al Jazeera, Google, and even the Pokemon Company to gain the trust of its targets, according to the researchers.”

The discovery and patching of the vulnerabilities in August probably slows down the NSO Group a bit. It won’t stop them, or any of the other companies working in the shadows to sell malware to the worst governments in the world.

Citizen Lab’s report is here, and there are fascinating writeups of the attack on Mansoor and the NSO Group here and here.

NSA targeted Cisco routers for years

Documents and hacking tools appeared online last month that exposed one of the NSA’s many secrets: it has been using hacking tools to take over Cisco firewalls used in “the largest and most critical commercial, educational and government agencies around the world,” according to a former NSA employee. Several of the tools used zero day exploits that had existed for years, allowing the NSA to intercept VPN traffic and potentially modify it on its way to its destination. The Washington Post reported that another former NSA employee said, “The stuff you’re talking about would undermine the security of a lot of major government and corporate networks both here and abroad.”

No one knows who leaked the documents online, but it’s clear that at least one other party besides the NSA had access to them. Hackers? Another government’s spy agency? Edward Snowden tweeted that “Circumstantial evidence and conventional wisdom indicates Russian responsibility.” (Worth noting that Snowden has nothing to do with this. A respected security researcher examined the material and concluded: “This is definitely not Snowden stuff. This isn’t the sort of data he took, and the release mechanism is not one that any of the reporters with access to the material would use. This is someone else, probably an outsider…probably a government.”)

Now that the tools are public, anyone can use it to hack Internet infrastructure that is not patched. These are professionally designed tools enabling attacks that can now be carried out by a much larger base of hackers. Cisco confirmed that the leak exposed an unknown critical vulnerability in a large number of its firewall devices. The evidence makes it obvious that people within the US government have known of the risk since at least 2013 and allowed it to persist.

Reports in the first few days suggested that the leaked tools could only be used against older Cisco devices, although that’s bad enough since there are many thousands of those older devices used in critical networks worldwide. It only took a few days for researchers to find a simple workaround for one limitation and add support for newer models, widening the scope of the exploit and making it a far bigger threat.

More information about the NSA hack here and here.

There are three lessons to learn from this collection of bad news.

(1) When hackers (“security researchers”) sell exploits to governments instead of reporting them to the developers who can fix the flaws, they make us more vulnerable.

(2) When governments keep zero day exploits secret, they make us more vulnerable.

(3) The only way to be safe from ninjas is to live a squeaky clean life that does not attract attention. Don’t become a target. It sounds easy to most of you, right? But it’s bad news if you’re a journalist or a human rights activist – and that’s kind of a big exception that ought to concern all of us.